No one is surprised when they learn that Yoga is more than a series of postures and breathing exercises. The best in-depth introduction to Yoga that I’ve ever found is from The Oxford Companion to the Body. I’ve included the text below.

The word ‘yoga’ refers primarily to an ancient Hindu spiritual tradition intended to overcome the narrow sense of individual selfhood, though its usage ranges from the very general to the specific and highly technical. The word is probably derived from the Sanskrit root yuj, which implies a yoke or harness, invoking the notion that when the ox and the cart are connected via the yoke, the resulting complex is greater than the sum of its parts. In its most general sense, yoga involves harnessing or integrating the forces of embodiment (mind, body, and spirit) in order to transcend embodiment.

Sometime around 200 bce, a man named Patanjali developed a system of yoga which ostensibly synthesized previous yogic traditions. It corresponds to a model of the human organism found in the sacred Hindu texts, the Vedas. This model is known as the ‘sheath’ model, and describes the human organism as a series of concentric sheaths or envelopes, all composed of matter of varying degrees of fineness or subtlety. The spectrum of human material ranges from the most crude or dense, to the most absolutely fine or subtle, and therefore the most ‘real.’ The goal of Patanjali’s yoga is to identify progressively with the finer aspects of one’s being until purification leads to identification with the True Self, residing at the core of the sheaths.

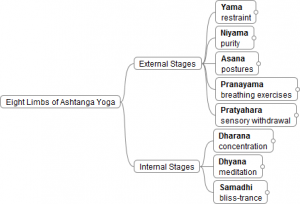

Patanjali’s yoga, sometimes called Raja or ‘royal’ or ‘grand’ yoga because of its broadly synthetic ambitions, involves eight steps or stages, of which the first five are considered ‘external’ and the last three ‘internal.’ This relates to the sheath model. In Indian medical theory, for instance, which also bases itself in part on the sheath model, disease always begins from the outside and works its way in, so that even mental illness is a form of physical illness that has progressed to the innermost sheaths. Healing, then, must also begin with the physical and proceed to the spiritual.

These eight steps of the yogic path are meant to be accomplished sequentially. That is, one masters the first, and adds the second. When the second is mastered, the third is added, and so on.

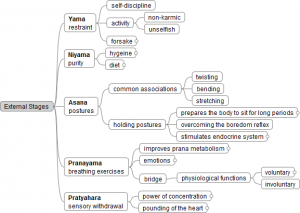

The first five or ‘external’ stages are:

Yama – Restraint

The path begins with self-discipline, or the adoption of a basic moral code of non-karmic or ‘unselfish’ activity. The yogi forsakes stealing, lying, cheating, killing, and other exploitative and self-gratifying behaviours.

Niyama – Purity

Purity involves both hygiene and diet. In terms of hygiene, radical ablutions or cleansing rituals are performed, such as swallowing a length of gauze and pulling it back out again, in order to scour the intestinal tract. Thus hygiene goes beyond the superficial conception of cleanliness which governs ordinary life. Diet is also important, since the outermost sheaths are composed of the food that we eat. Dense foods such as meat are to be avoided, and subtle, refined foods are to be preferred. Also important are the mode of preparation and the sizes and times of meals. Fasting is also an important purity practice, but is seen as a hygienic concern, and not a dietary one.

Asana – Postures

The twisting, bending, and stretching that are commonly associated with the practice of yoga serve a number of purposes. The holding of postures prepares the body to sit for long periods of time in meditation, enables the overcoming of the boredom reflex, and is held to stimulate the endocrine system and thus to be important, since the endocrine system affects our emotions; this stage of yoga begins to affect the emotional as well as the physical sheaths.

Pranayama – Breathing Exercises

Prana is the life force which enters the body with the breath and which is metabolized from the foods we eat. Breathing exercises improve the ability of the body to metabolize prana. Also, since breathing affects emotions, breath work helps to regulate and refine the emotional sheath. Finally, breathing also represents a bridge between those physiological functions which we believe we can control (voluntary) and those which we cannot (involuntary). Adept yogis claim to be able to control metabolism, reflex, and brainwave activity — events slow or virtually stop the heartbeat.

Pratyahara – Sensory Withdrawal

At this stage, the yogi is able to use the power of concentration to withdraw attention and identification from the outermost, physical, ‘external’ sheaths. This means that sensory input is blocked out or ignored through an effort of will. The only sound one hears is the pounding of the heart, and this explains why a yogi might want to slow or stop the heartbeat, in order to establish true peace and quiet and facilitate inwardness.

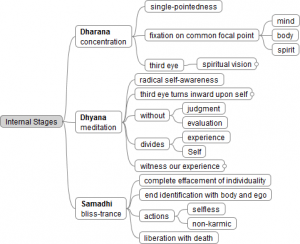

The last three, or ‘internal’ stages are:

Dharana – Concentration

Concentration in this sense involves what is described as single-pointedness, that is, the fixation of mind, body, and spirit on a common focal point. Here, the image of the third eye is invoked to suggest the strengthening of spiritual vision to the point where it is capable of sustaining a single object for long periods of time, like an eye staring at an object.

Dhyana – Meditation

Dhyana refers to meditation, or a sense of radical self-awareness. To return to the metaphor of the third eye, once it has been trained to stare unblinkingly at a single object for a long period of time, it then turns inward upon itself, watching itself watch itself. This awareness takes place without judgment or evaluation, and drives a wedge between our experience and our Self. We watch or ‘witness’ our own experience as though it were only virtually real, as though it were a drama or play. We cease to identify with it.

Samadhi – Bliss Trance

This condition is one of complete effacement of individuality. One no longer identifies with one’s body or ego; one’s actions are selflessly motivated and non-karmic. This virtually guarantees that liberation will occur with death, which will take place once the consequences of past karmic action have been borne.

This text is from The Oxford Companion to the Body.

Leave a Reply